We humans think we’re pretty special as far as animals go, and one thing that makes us unique is our ability to communicate super complex ideas through language and, ultimately, speech itself. Human speech is an important part of everyday life but not one that should be taken for granted.

Let’s look at the anatomy and evolution of speech and why humans can talk while other primates like chimpanzees can’t.

But before we dive in, let’s make sure we’ve got our definitions straight: speech is the production of sounds to communicate, while language is the system of words we use to communicate with each other. Speech is spoken language, but language can exist without speech (like the written language you’re reading right now).

First, let’s do a quick overview of the anatomical structures that make speech happen.

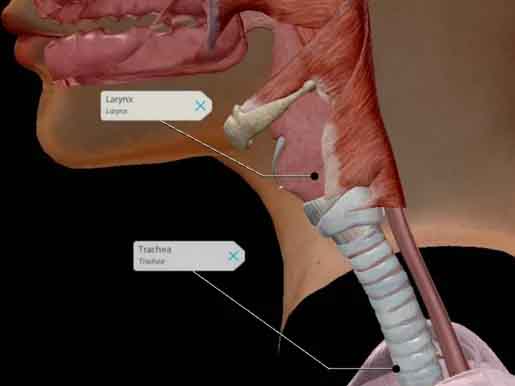

During exhalation, air travels from the lungs into the trachea, also known as the windpipe. At the top of the trachea is the larynx, and the larynx contains bands of tissue known as vocal cords or vocal folds.

Contracting the muscles in the larynx allows us to manipulate the vocal cords. By altering the tension of the vocal cords and the amount of space between them (aka the glottis), we can control the pitch, volume, and tonal quality of the voice.

There are nine muscles in the larynx that affect the vocal cords and glottis:

The larynx isn’t the only structure that impacts speech—it’s time to talk about the tongue. By coming into contact with the oropharyngeal wall, soft palate, and hard palate, the tongue can impede airflow.

Vowel sounds are made by changing the shape and size of the space the air passes through—tongue height, position, and roundness of the lips all contribute to the vowel sound we make.

Consonants, on the other hand, involve the stopping and releasing of air; airflow can be impeded at the lips, teeth, alveolar ridge, hard palate, soft palate, uvula, oropharyngeal wall, epiglottis, and glottis.

At birth, humans actually have a vocal tract similar to nonhumans. As the infant develops, the roof of their mouth flexes, the tongue moves lower into the pharynx, and the larynx descends.

However, speech doesn’t start in the lungs or the larynx; it starts in the brain. The brain has to remember the sequence of speech sounds before a word can be spoken, so it generates a mental representation of those sounds. That mental picture is turned into motor commands that the brain sends to the muscles to alter airflow and make the correct sounds.